Tour 8 Section B - East Liverpool to Marietta

State Route 7

Making our way down State Route 7 from East Liverpool in the late afternoon, it is easy to understand why TOG refers to Wellsville as a “dingy city” where “boxlike houses stand beside redbrick sidewalks.” Though the new Route 7 necessitated the removal of the “dwellings [which] thrust themselves out from the steep hillsides,” the tops of those hills are still there, throwing the entire town into shadows much earlier than the admittedly similar-looking West Virginia hamlets on the opposite shore. As we passed above the town on the elevated highway, Wellsville seemed anything but. To be fair, if we had been traveling the same route in the morning when it was the Ohio side enjoying the healing sunlight, we may have been more inclined to investigate TOG’s claims of dinginess.

Ohio in Shadows while West Virginia Glows, 2012

Main Street, Wellsville, 2016

There are a few spots between East Liverpool and Marietta where one can find remains of the old Route 7, but generally the road no longer “dodges along the Ohio River…sweeping around jutting headlands, throughout fertile bottoms, past scores of towns and cities.” Instead, it is often a raised four-lane highway that cuts through the landscape as if it can not be bothered with such needless sight-seeing. If I lived along the Ohio, I would certainly be thankful for the improvements that allows one to get from East Liverpool to Steubenville in twenty-minutes rather than the hour or two it took before the road improvements began in the 1960s . But unlike the writers of TOG who seemed to be constantly aware of “the moods of the river which change with the season and the weather,” we drove above it without giving it much thought.

Old Route 7 near Yorkville, 2012

Just how different the road is can be illustrated by the fate of Memorial Point (whose existence I found evidence of in the manuscript files, rather than TOG). When the road was completed in 1932, a “tall, steel flag pole” was erected on the “highest point on S 7 along the river.” At this point, approximately six miles from East Liverpool, drivers were “afforded an expansive view of the river and the valley.” Today, there is no indication of the flag pole or even the specific hill on which it stood. In fact, as the picture below shows, the upgraded Route 7 roadway cuts through what appears to be the highest point in the area just before it crosses Yellow Creek.

Possible Site of Memorial Point, 2012

Road Construction on new Route 7 near Steubenville, 2016

Before the new roadway was put in place, this Yellow Creek crossing was memorialized in postcards for being a picturesque site where interurban, train, and roadway bridges all spanned the river. Run by the Steubenville East Liverpool and Beaver Valley Traction Company, the interurban was part of a massive system of public transit that covered the state. One can imagine how different this stretch of Ohio might look if, rather than investing money in the expanding of Route 7, the transportation authority had put its efforts into revitalizing the interurban rail system. Rather than isolated hamlets whose exits one can easily ignore because of uninviting light, towns like Wellsville, Empire, and Toronto might have enjoyed consistent visitors and commuters, sharing populations and resources, creating a more dynamic regional economy. As it happened, the rail line stayed, the road was upgraded, but all that is left of the interurban that crossed Yellow Creek is some concrete rubble lying between the other two bridges.

Three Bridges Crossing Yellow Creek, 2012

Yellow Creek

In addition to being the location that James and Daniel Heaton first set up their smelting furnace (see section A of this Tour), Yellow Creek, as TOG tells us, was the site of Mingo Chief Logan’s cabin. Logan, identified variously as Tah-gah-jute, Tachnechdorus (also spelled “Tachnedorus” and “Taghneghdoarus”), Soyechtowa, Tocanioadorogon, James Logan, and John Logan, was the son of Shikellamy, an important Iroquios diplomat. When he moved to the Ohio Valley in the 1760s, Logan took up residency with other Iroquois, mostly Senecas and Cayugas, who became known as Mingos to the white settlers in the area.

In 1774, a Virginian named Daniel Greathouse lured about a dozen Mingos across the Ohio River to the cabin of Joshua Baker, a trader in the region. Here Greathouse murdered the Indians, including Logan’s brother, as Greathouse’s men repelled the canoes sent from Yellow Creek to aid the stranded Mingos. In response, a number of war parties, including one led by Logan, attacked settlers along the Virginia frontier prompting the Royal Governor, Lord Dunmore, to send an expedition against the Mingos and Shawnees. The Indians eventually agreed to peace after the only major battle of “Dunmore’s War,” but Logan refused to participate. Instead, according to many colonial newspapers and Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia, the war chief issued the following statement:

I appeal to any white man to say, if ever he entered Logan’s cabin hungry, and he gave him not meat; if ever he came cold and naked, and he clothed him not. During the course of the last long and bloody war, Logan remained idle in his cabin, an advocate for peace. Such was my love for the whites, that my countrymen pointed as they passed, and said, Logan is the friend of the white men. I have even thought to live with you but for the injuries of one man. Col. Cresap, the last spring, in cold blood, and unprovoked, murdered all the relations of Logan, not sparing even my women and children. There runs not a drop of my blood in the veins of any living creature. This has called on me for revenge. I have sought it: I have killed many: I have fully glutted my vengeance. For my country, I rejoice at the beams of peace. But do not harbour a thought that mine is the joy of fear. Logan never felt fear. He will not turn on his heel to save his life. Who is there to mourn for Logan? Not one.

Beyond incorrectly pointing the finger at Col. Cresap, Logan’s speech was most likely not spoken by Logan at all, at least not in this form. Instead, it was probably one of the first examples of a genre that became known as “Aboriginal Eloquence.” Thomas Guthrie argues in a recent volume of Ethnohistory that the celebration of Indian oratory –systematically referred to as ‘eloquence’ by nineteenth-century Americans – was in and of itself a form of subjugation.

The way Euroamericans interpreted and celebrated Indian speech and produced and circulated texts of Indian oratory precisely positioned Indian subjects in this predetermined framework. Indian eloquence, inextricably tied to primitiveness, confirmed that Indians as a race were doomed and dying; the more eloquently they spoke, often uttering their own elegies, the more certain was their passing. In other words, Euroamericans set up an Indian that they could justifiably defeat by putting words in his mouth.

–Good Words: Chief Joseph and the Production of Indian Speech(es), Texts and Subjects,” Ethnohistory 54 no.3 (2007), 536.

Regardless of the speech’s veracity, Logan became an important historical figure in Ohio’s origin story and there is now a monument at the approximate location of his cabin imploring readers to remember his past:

Lest We Forget Chief Logan

“Tah-Gah-Jute”

A Chief of the Mingoes

A Friend of the Whites

From near this place in 1774, all the family of Logan was lured across the Ohio River and massacred by whites thus sending Logan and Ohio Indian nations on a path of war for vengeance now known to history as Cresap’s War.

“Who Shall Mourn”

There is no date on the monument and its exclusion from TOG indicates that it was unveiled after the guide’s publication, though its creation would not have been a surprise for TOG’s creators. According to James Bishop who wrote one of the manuscript guides for the area, the spot is “second only to Mingo Junction in historic lore.”

I only ran across the monument’s existence because of a great site called the Historical Marker Database. Even with the information on the database, however, it took me fifteen minutes to locate the marker in a rest stop about the size of a baseball infield. Lets see if you can do better in the picture below.

Logan's Monument, 2012

Still can’t find it? How about this one?

Logan's Monument and Trash Can, 2012

Standing at the shelter, looking west toward the monument and the trash can placed equidistantly from the path, there is nothing to indicate that there is anything of note on the front of the squarer of the two cement posts. If the idea was to make the monument blend into the landscape, the caretakers have done an excellent job.

Directly across Route 7 from the rest area is a small field separating the road from the railroad tracks and the Ohio River. This field was the backyard of the McCullough -Jefferson County Children’s Home which cared for over 2,500 kids between 1914 and 1958 when it was torn down to make room for the new road. According to James Bishop’s manuscript guide, the “light colored brick home was made possible because of the philanthropy of William G. McCullough who donated the old homestead farm for the purpose of a home for destitute children and supplemented the gift with $40,000 in 1909.”

McCullough Children's Home of Jefferson County, @1940 / copyright Ohio Historical Society

Former site of McCullough Children's Home, 2012

Power Plants

The towns of Stratton, Empire, and Port Homer were, at the time TOG was published, known as clay-manufacturing towns, the latter two home to the Empire Sewer Pipe Company and the Peerless Clay Manufacturing company respectively (According the the manuscript tour, Empire was originally named in 1850 when “captain James Young came to the village and brought with him a flock of Shanghai chickens and the town was given that name.” One must assume that the author meant that the town was named in honor of the fowls’ city of origin rather than the birds themselves, but I can’t imagine a better name than “Shanghai Chickens, Ohio”). These towns have essentially merged into one community where the local economy is still based in extractive resources, but those resources consist of coal rather than clay.

The scale of the industrial structures on both sides of the Ohio is impressive. Between the blast furnaces, refineries, and power plants, the magnitude of engineering is awe-inspiring. Sprawling steel and concrete forms cover the landscape as if a massive seven-year-old boy has left his erector-set creations scattered across the valley after being called in to supper by his equally-massive mother. Yet even in this industrial landscape, the size of the W.H. Sammis power plant in Stratton is jaw-dropping. As you approach the structure which straddles Route 7, you can imagine how Jonah might have felt if his whale was made of concrete and it spouted smoke instead of water.

Since coal was discovered in the region in the beginning of the nineteenth-century, it has shaped the economy and the environment of northeast Ohio. This is still the case. FirstEnergy, which owns the W.H. Sammis plant, comprises the nation’s largest investor-owned electric system, serving 6 million customers within a 67,000-square-mile area of Ohio, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Virginia, Maryland, New Jersey and New York. In 2007, FirstEnergy ranked 212 on the Fortune 500 list of the largest public corporations in America. It also ranked as the 58th largest polluter in the country, according to a study done by the University of Massachusetts.

Ohio Edison, a subsidiary of FirstEnergy which owns the plant, eventually reached a settlement with the EPA and the justice department requiring them to spend $1billion to reduce harmful emissions. Ultimately, the scrubbers and selective catalytic reduction equipment cost $1.8 billion and five years to install but has been successful reducing emissions of sulfur-dioxide by 95 percent, nitrogen oxides by up to 90 percent, and mercury by about 75 percent. The retrofit was named Construction Project of the Year by Platts Global Energy Awards in 2010 and received an honorable mention from Power Engineering magazine. Cardinal Power Plant (owned by AEP, FirstEnergy’s rival) a few miles down the road in Brilliant has also gone through a number of retrofitting projects.

A few good 3-irons south of the the Sammis plant is the site of the former Ohio Edison plant it replaced. When it was completed in 1926 at a cost of $8,000,000, the Ohio Edison was one of the largest power plants int the country with an capacity of 350,000 horse power. Today, the Sammis Plant’s capacity of 2,233 megawatts is equal to 2,994,502,326,066 horse power. On google maps, the Ohio Edison plant still stands but when we reached it, only a few outbuildings remained.

Toronto

Looking south from the Ohio Edison site is a smokestack at a much more human scale than the towering Sammis’ monoliths. Though it was once part of the “largest plant of its kinds on the Ohio river,” the 40-ft smokestack of the now-abandoned Kaul Clay Company virtually invites you to explore what lies at its base. Unlike the anonymous cement tower of the Sammis Plant, the stack of the Kaul Company proudly displays its ownership with the word “KAUL” built directly into its brick. According to the manuscript guide, the stack was part of the 25 kilns that fired 100 tons of raw clay every day, “making pipe that varies in size from three to thirty six inches as well as sewer pipe, flue lining, and conduits.” Three hundred men were employed in the entire operation at its peak.

Today, a sign at the entrance to the site informs us that Jefferson County is applying for a Clean Ohio Assistance Fund Grant to pay for an environmental assessment of the property. The town of Toronto could certainly benefit from developing this site that now offers only bored teenagers and wildlife a place to congregate (A beautiful coyote bounded into the bushes as I made my way up the main path to the stack). Yet, unlike those who have a reason to grow nostalgic over the loss of the actual clay-factory and the economy it supported, I found myself lamenting the possible passing of this liminal site that was neither in-use, nor fully reclaimed. There is something wonderful about walking the grounds of such a site, feeling like the first one to find a pile of clay piping or the filled-in entrance to one of the clay mines behind the kilns, imagining how the whole operation might have come together. Unlike running across the furnace in East Liverpool which, even with its minimal signage, felt as if we had stumbled across a neat historical monument, walking around the Kaul furnace felt more like discovering history.

As someone who feels very strongly about the importance of public history, I am certainly not advocating the removal of historical markers or arguing that there should be less attention paid to maintaining historical sites. There is a certain thrill, however, of creating your own, unencumbered vision of what might have happened in any given spot before you arrived there. Like the junky lot behind Mr. Sneelock’s store in which Dr. Seuss’s Morris McGurk created his imaginary Circus McGurkus, the remnants of the Kaul Clay Company give us just enough reality to let our historical imaginations run wild.

Further downtown was the site of the Toronto Fire Clay Company. Spread over sixty acres, TOG informs us that “grey dusted factory and storage rooms and the behive looking kilns,” produced an array of clay products including Toronto Faced Brick; the much-sought after brick “used around the plaza of the Supreme Court … the American Federation of Labor, both of Washington, D.C.” Just as significantly, according to author and Toronto historian Bob Petras, Toronto Fire Clay was the first company to manufacture sewer pipein the western hemisphere, after which the region became known as the sewer pipe capital.

However, epitomizing the narrative the manuscript guide gives us in 1939 of a “fading clay industry” giving way to “giant electrical power plants,” many of the independent clay companies were razed to make way for the Ohio Edison and Toronto Power plants. By the middle of the nineteenth-century, only a few of the larger companies remained. The last of these was the Kaul Clay company which closed its doors in 1981, unable to compete with new plastic and fiber pipes.

While the remains of the Kaul Company still exist, the area at the end of Fifth Street that was the site of the Toronto Fire Clay Company has been partially developed into low-income housing and the municipal building, though a large, mostly abandoned structure was probably part of the industrial site.

One site that is still in use is that of the Follansbee Brothers Steel Mill. According to the manuscript guide, Follansbee brothers was “an ideal and complete unit for the production of sheet steel produced by the Drop Forge method,” when it was built in 1918, but is “waiting modernization.” Those changes have certainly taken place as the site now houses Timet, one of two titanium manufacturing companies in the country.

Half Moon Bend Near Steubenville, @1940 / copyright Ohio Historical Society

Half Moon Bend North of Steubenville, 2012

Steubenville

“Steubenville,” according to TOG, “has a historical depth that extends beyond the almost legendary period when Fort Steuben was erected in 1787 to protect the survey of the Seven Ranges….Like Marietta and Chillicothe, it was one of the mother towns of the state.” Yet by 1940, that history had been largely forgotten under the weight of the booming steel industry. “Steubenville speaks the language of the metropolitan Pittsburgh area: the talk of steel mills and the river, of polyglot Irish, Welsh, English German, Slavs and Latins, and the baseball fortunes of the Pittsburg Pirates….Events outside the circle of mills are dwarfed and seem incidental.” In 1940, half of the cities 40,000 residents worked in steel mills, driving a retail business consisting “over five hundred stores…stocked with three million dollars worth of goods from the markets of world, sufficient in volume and variety to meet every consumer demand,” according to the manuscript guide. This trade “employs more than two thousand workers who make shopping attractive and pleasant.”

Covering over a mile of the Ohio riverfront was one of the Wheeling Steel Corporation Plants. Here, nearly 7,000 workers produced coils, bars, and sheet pipe. In addition to the two blast furnaces, 11 open-hearth mills, and hot-strip mill, the company owned its own railroad cars which traveled back and forth over the Ohio River on the company-owned bridge to a byproduct plant on the West Virginia side. Despite its size, however, Wheeling could not avoid the fate of so many other steel mills and, after a series of mergers and take-overs, Wheeling Steel closed the doors to its Steubenville plant in August of 2009.

Bridge and former byproduct plant of Wheeling Steel, 2012

Wheeling Steel Through Trees, 2012

Perhaps the closing is temporary, as the company (which is now Severstal) contends. Unlike the barbed wire and “no trespassing” signs which clearly indicate the state of the Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company, the former Wheeling Plant looks as if it might simply be closed for the weekend. As such, I did not hold up much hope that the owner of the security truck parked beside gatehouse would simply wave me through. Much to my surprise, there was no one around. After waiting a few minutes to see if someone was going to come question me, I let myself in. Below is some of what I found.

Downtown Steubenville

When the steel industry collapsed, it took Steubenville’s accompanying retail business with it. No longer were the streets “thronged with people from surrounding communities seeking business and social contacts.” As Leonardo and I walked throughout the heart of the commercial district, we were met with more “out of business” and “call for an appointment” signs than open doors (though the Chinese restaurant and a gyro shop that are the entirety of the dining choices in downtown Steubenville are both surprisingly good). Today, Steubenville residents earn $4,000 less than the national per capita average and over 20% of its 18,000 residents are unemployed.

Despite this depression, there is an ineffable beauty to Steubenville. As TOG acknowledged seventy-five years ago following a different economic collapse, “there are in town strange glimpses of beauty that are foreign to Steeltown: an unexpected view from the steep green slopes above the mills; of the sun creeping up over the West Virginia hills; or of a steamer, bound down the river at sunset, churning a long golden wake past the stark walls that line the banks.”

Beyond the picturesque, the urban infrastructure of Steubenville has an unmistakable charm that can be found under the veneer of disrepair. Because Steubenville simply does not have the money to either renovate or raze unused structures, many of the streets are lined with wonderful old buildings. A few of which, most notably the Grand Theatre, have attracted local preservationists, but most lie empty, waiting for better times to come along.

Grand Theatre and National Exchange Bank and Trust Building, @1940 / copyright OHS

Grand Theatre and Chase Bank, 2012

The corner of Sixth and Market Streets has seen some drastic changes however, much to its detriment, including the destruction of the Imperial Hotel (Notice on the far left side of the newer image, a mural of a street scene reminiscent of the the original photograph).

Sixth and Market Street, @ 1940 / copyright OHS

Sixth and Market Streets, 2012

That the only civic construction project we ran across as we walked through the city was one lonely hammer pounding away inside the Grand Theatre highlights one of the ironies of Steubenville. As the collapse of the steel industry became a reality in the late 1970s and early 80s, a small group of artists began to decorate the walls of crumbling downtown building with murals celebrating the city’s history. Steubenville was soon re-christened the City of Murals as tourists brought much-needed dollars to the depressed town. Over the past ten years, various organizations have donated money to help restore and maintain the murals.

Yet it is difficult to ignore the fact that Steubenville’s economy has not moved much beyond the period these murals represent. It is as if the town is nostalgic for a period it can’t quite escape. As I walked by a hand-painted sign for Coca-Cola, I wasn’t sure if it was a new mural or simply an old ad that had not yet given in to the ravages of time.

These murals are not in TOG of course, but the one above represents a building that is in the manuscript guide. The following passage gives us a small but intriguing glimpse into race relations in Steubenville in 1940: “On the southwest fringe of the business section is one of the negro districts of the city. Two other negro centers are on North Eighth Street and Wells Street. …[D]uring the World War and the consequent labor shortages, there was a marked increase in negro population. The City Board of Recreation maintains the Central Recreation Center at Tenth and Adams streets exclusively for the Negro population. It consists of a large recreation hall, swimming pool, game and picnic sites.” Nothing is left of the recreation center itself which sat at the corner of Adams and Tenth Streets.

In addition to its commercial history, Steubenville has also tried to highlight aspects of its residential heyday. In contrast to East Liverpool in which wealthy business owners lived above the dust of the clay mills in the hills south of town, Steubenville’s elite lived in what were once lovely victorians in the heart of the city. Like the murals, however, the celebration of the “Historic North Fourth Street” district walks a fine line between acknowledging the city’s history and highlighting its inability to escape it.

istoric North Fourth Street District, 2012

Historic North Fourth Street Victorian, 2012

One downtown building that is in good shape is the main branch of the Public Library of Steubenville and Jefferson County. TOG refers to it as the Carnegie Public Library after its primary benefactor, but regardless of the name, it remains a handsome building “built of trick and terra cotta in mission style with a dash of Tudor in the trimmings.

Steubenville High School did not make the final cut of TOG, but the manuscript guide points out that it was the largest single unit of the Public Works Administration in the state of Ohio in 1939. Built at a cost of $1,000,000 with beautiful art deco details, the school was expanded to include the adjacent War Memorial Building sometime since the manuscript guide was written.

Main Branch of the Steubenville Public Library, 2012

Steubenville High School, 2012

1937 Ohio River Flood in Steubenville

Between January 13 and January 25, 1937, 12 inches of rain fell on the watershed of the Ohio River. The river, nearly 30 feet above flood stage in some areas, wreaked havoc on towns stretching from Pittsburgh to Cairo, Illinois, killing 385 people, and causing $500 (1937 dollars) worth of damage. The Ohio Guide Photograph Collection has a wonderful assortment of images documenting the disaster, including those below of Steubenville which I have rephotographed.

1937 Ohio River Flood of Steubenville, 1937 / copyright Ohio Historical Society

Wheeling Steel from Steubenville Railroad Bridge, 2012

937 Ohio River Flood - Pennsylvania RR Bridge, 1937 / copyright OHS

Steubenville Railroad Bridge, 2012

As I post the above picture of the Pennsylvania Railroad Bridge, I realize that I was not in the same location as the 1937 photographer. I should have been standing another twenty feet behind where I was, which would have given me 15 feet more elevation. The earlier shot must have been taken from the old Route 7 which may have sat a few feet lower than it does now, but certainly higher than the spot on Water Street from where I took my picture. In fact, despite being a good 12 feet above the river when I took the shot, I would have been quite wet in 1937. The guard rails of Water Street are clearly visible in the old picture, as is the telephone pole that would have been on the river side of Water Street, essentially marking the spot where I would take my picture nearly 75 years later.

Perhaps the most dramatic picture of the Steubenville flood in the collection is not of the Ohio River at all, but of Willis Creek, a tributary of the Ohio on which the Steubenville Pumping Station sat. The photograph is not that dramatic until one visits the site. The pumping station sits a few hundred feet above the Ohio River, so all of the water visible in the photograph was from a creek that is so inconspicuous that I was never able to find it, despite knowing its location (though the sheer bulk of the new Route 7 was also to blame).

The pumping station itself is also easy to miss as it is largely hidden by the new road. In fact, the only shot I could manage that was reasonably close to the Ohio Guide photograph was taken from Google street view.

1937 Ohio River Flood - Steubenville Pumping Station, 1937 / copyright OHS

Steubenville Pumping Station from Google Street View

The scene seemed so impossible that it took may comparisons to verify that they were indeed taken at the same location. Despite the missing roof and entire second story of the building however, one can still make out where the second set of windows were, as well as the words “Steubenville Water Works” above the door. The location of the building and the landscape itself also reaffirms the conclusion that this was the pumping station, “2 miles north of Steubenville” as the back of the original photograph informs us.

Close up of Steubenville Pumping Station

Steubenville Pumping Station, 2012

Jefferson County Courthouse

The pumping station is not the only building that has lost some of its height. In fact, buildings losing their upper portions seems almost epidemic in Steubenville. The Jefferson County Courthouse, TOG informs us, was a “soot blackened Romanesque building of sandstone, 150 feet long as it is high.” The building is now neither soot blackened nor properly proportioned. Completed in 1874, the six story structure included a massive clock and bell tower which visitors could enter via a beautiful spiral staircase. After the tower collapsed during a snow storm in 1950, county officials decided to cut their losses and replaced it with a flat roof. The bell now sits in a park across the street and it is the statue of Justice which still sits atop the peak of the pediment that is the focal point of the building.

The building was the third to sit on this site, according to the manuscript guide. “The first was a structure of logs and the second was a fine brick building.” The building of the new sandstone courthouse, “foretold the coming of a new and different age, the passing of an agrarian and handmade goods economy, and the coming of a mass production in which steel would be the leading factor.” If the construction of a new Jefferson County Courthouse foretold the coming of “new and different age” based in steel, the collapse of its’ bell tower illustrated the tenuousness of that industry.

Jefferson County Courthouse-Base of Tower, @1940

Jefferson County Courthouse, @1940 / copyright OHS

Jefferson County Courthouse, 2012

Steubenville Churches

It was not just the courthouse and the pumping station that lost towers and roofs. After the losing its four-sided peak, the naked tower of what was originally the Hamline Episcopal Church now resembles the crenelated walls of a Medieval Times restaurant. The church was built in 1847 as a home for breakaway parishioners of the South Street Methodist Church which was itself first established after an 1803 visit of Bishop Frances Asbury. It now holds the Sycamore Tree Church, one of thirty-seven Methodist churches in the Steubenville metro area according to usachurches.com.

Hameline Episcopal Church, @1940 / copyright OHS

Sycamore Tree Church, 2012

TOG does not usually include churches in its points of interest and Steubenville is no exception. Perhaps because of the sheer number of them however, (usachruch.com list 48 within the city limits) the OHS Guide Photograph Collection contains what seem to be an inordinate number of pictures of Steubenville houses of worship. There is a photograph, for example, of the “First M.E. Church of the Seven Gables, built in 1814,” according to the note scribbled on its back. Cavalry Methodists worshipped there at the beginning of the twentieth century before it became the Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church in 1946, making it first Greek church in town (sometime after which it too lost the top to its tower). The Second United Presbyterian church similarly changed its name to Covenant Presbyterian Church though did not lose its tower, mostly because it never had one to lose.

First Methodist Episcopal Church of Seven Gables, @ 1940 / copyright OHS

Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church, 2012

Second United Presbyterian Church, Steubenville, @1940 / copyright OHS

Covenant Presbyterian Church, Steubenville, 2012

Despite the number of churches, at least one person thinks that the residents of Steubenville could use further affirmation of their faith. There seemed to be no direct correlation between the quickly descending numbers on the sign across the street and the poster taped to the call box, but Leonardo and I crossed the street before it struck zero just to be safe.

Angel’s Trail and Ohio Valley Lookout

While its name was Angel’s Trail, TOG tells us that the path whose entrance was “opposite 274 Belleview Blvd” was used for more earthly concerns. It was “an old lover’s lane given modernity by concrete steps.” Leonardo and I searched in vain for the entrance as Belleview Blvd is a maze of turns, starting and stopping for no apparent reason at various points on the hills above Steubenville. Google maps was no help as there is no 200 block of Belleview listed. I ultimately found the steps on my second trip to Steubenville by climbing up from the bottom of the hill, past an abandoned Catholic church at the end of North 9th street. After I understood what I was looking for, I would notice other paths criss-crossing the hills above the city.

These paths were once well used, both by people walking to and from town and by visitors who want to take in “the panorama of Steubenville.” According to the manuscript guide, the panorama from the top of Angel’s Trail included “a medley of church spires and towers, smokestacks, and the barren bluffs of West Virginia rising abruptly from the waters edge.” At some point in the last twenty years, however, the city simply couldn’t afford to maintain the trails. Signs now clearly spell out the fate of Angel’s Trail, though their placement and irregularity indicate only a half-hearted attempt to deter people from entering, .

Closed" 2012

Angel's Trail, 2012

Climbing the first hundred feet of the trail, the steps are cracked and uneven but they are relatively useable. After that, however, the trail becomes an obstacle course of downed trees, broken slaps of concrete, and mud. When I reached what appeared to be the top, there was no longer an “entrance surrounded by hemlock and second-growth trees,” but a pile of concrete that fizzled out into the property of a private residence. Where one once viewed the “panorama of Steubenville,” I saw a few feet of the path I had climbed.

"Panorama of Steubenville", 2012

Steubenville Looking Toward Ohio River Postcard, @1940 / copyright OHS

This was not always the case. The Ohio Guide Collection contains a postcard with a vantage point nearly identical to the above photograph. Similarly, the manuscript guide informs us that the “Ohio Valley Lookout,” half a mile south of Angel’s Trail, affords an even grander view; “To the north can be seen the winding Ohio River, spanned by the railroad bridge, Market Street Bridge, and backed by the hills of West Virginia and further south, the private bridge of the Wheeling Steel Corporation.” While I was able to glean a partial view by climbing down an embankment behind Trinity Hospital, it was not easily accessible and certainly not something TOG would have recommended. The larger implications of these stunted views would not be clear to me until the we reached Marietta the next day.

Beatty Park

Though its creation in 1930 was one of the events that were “dwarfed and incidental” to Steubenville’s steel industry in the estimation of TOG’s editors, they still included Beatty Park as one of the city’s twelve points-of-interest. Along with its “100 acres of picnic sites and camps for auto-trailers,” the park provided “a full-time worker” to take charge of the city’s recreation programs which included “baseball, swimming, golf, and other sports.”

For most of the last twenty-five years, Beatty Park faired as poorly as other public spaces such as Angel’s Trail and the Ohio Valley Lookout: the pool was filled in; the picnic spaces and camping spots were over-taken by weeds; and the shelter built by the Civilian Conservation Corps was reclaimed by the hill it sat on. However, thanks to the work of a few dedicated individuals and the Steubenville Parks and Recreation Department, Beatty Park opened to the public once again in 2007. Though its formal activities are much more limited than they were, the addition of a highly-acclaimed disc golf course has brought some life back into this once-popular recreation area.

Union Cemetery

The most scenic of Steubenville’s public spaces is Union Cemetery. It is now at least 25 acres larger than the 121 acres listed in TOG, but is still “covered with virgin timber.” The cemetery is made up of dozens of unique sections, some of which are tucked into hollows while others command views of the river. “Among those buried here are three of the ‘Fighting McCooks’ of Civil War fame,” TOG explains, though I had to go to Wikipedia to find out that the McCooks were a family of fifteen who gained fame for their deeds (and deaths) for the Union army.

As you may expect for a cemetery, the entry gates have not changed much in the past 75 years. Very soon after the below picture was taken, however, a row of “oriental plane trees” was planted and a “rough sandstone bearing a metal plaque inscribed with the names of those for whom the oriental plane trees were donated,” was placed a few feet west of the entrance. I do find it difficult to believe that this rock tucked under the trees just out of the frame to the right is a “3,000 pound boulder,” as the manuscript guide claims.

Union Cemetery in Steubenville, @1938 / copyright OHS

Union Cemetery in Steubenville, 2012 / copyright David Bernstein

"3,000 Pound Boulder," 2012

Bridges

After Angel’s Trail and Union Cemetery, the next two points-of-interest in TOG are the Fort Steuben Suspension Bridge and the Pennsylvania Railroad Bridge. Bridges have become so ubiquitous that we don’t give them much thought, but their frequent inclusion in TOG reminded me just how massive these projects were. When the the Pennsylvania Railroad Bridge was put in a single unit in 1936, its 1,000 foot span had to be fabricated and welded on the spot. It was then lifted into place by 10 hydraulic jacks and placed on new piers. The massive metal riveted cantilever through truss bridge looks very similar to what it did when it was installed.

Steubenville Railroad Bridge, @1940 / copyright OHS

Steubenville Railroad Bridge, 2012

The Fort Steuben Suspension Bridge did not fair so well. Almost twice as long as the PRR Bridge, the fate of the Fort Steuben Bridge was perhaps foreshadowed by the fact that it was build in 1928 at a cost of $2,500,000 but was sold to the state of Ohio for $1,000,000 just ten years later. It served as the main thorough fare over the Ohio in the region and by the nineteen eighties had begun to show structural damage. In 1990, the six-lane Veterans Memorial Bridge was built just to its north and in 2006 a weight-limit was put on the two-lane bridge. There were some attempts to turn it into a pedestrian walkway once it was clear that the Fort Steuben Bridge was no longer viable for motor vehicles, but these plans never materialized. When we drove into town, signs indicating its 2009 closure still remained, though it had been demolished three-weeks earlier. One of the piers was apparently left standing for posterity.

Sign With PRR Bridge and Veterans Memorial Bridge, 2012

Fort Steuben Bridge, @1940 / copyright OHS

Fort Steuben Bridge Pier, 2012

Many of the bridges connecting Ohio and West Virginia face a similarly tenuous fate. With fewer economies based on either side of the river, and highways in both Ohio and West Virginia making travel north and south much less taxing, there is no need to maintain so many crossings. While some have been demolished, others like the Bellaire Bridge remain in legal limbo and have become literal bridges to nowhere.

Bellaire Bridge, 2012

Ohio River Dam #9 and #10

Like its bridges, the locks and dams of the Ohio River have also changed since TOG was published. In 1910, congress enacted the Rivers and Harbors Act which allowed for the canalization of the Ohio River to a constant depth of nine feet. Completed in 1929 at a cost of over $100 million dollars, the project necessitated the production of 51 wooden wicket dams and 600 foot by 110 foot lock chambers along the length of the river. These structures included a brick powerhouse and two lock keeper houses. According to the manuscript guide, these were the the largest such locks in the United States with a total tonnage of over 15 million in 1925.

During the 1940s, a shift from steam propelled to diesel powered towboats allowed for tows longer than the 600 foot locks could contain. The barges now needed to be locked in two phases, which quickly proved untenable. In 1950, Corps of Engineers initiated the Ohio River Navigation Modernization Program which replaced the outdated wicket dams with structures of concrete and steel. Attached to each non-navigable dam were two adjoining locks, the larger of which being a 1200 foot by 110 foot chamber to accommodate fifteen barges that can lock through in one maneuver.

The new Pike Island Dam made the both Government Lock and Dam #9 (just a few miles south of the Ohio Edison site in Toronto) and Dam #10 (Steubenville) obsolete when it was completed in 1965. The older dams were demolished in 1975. Nothing remains of site #9 but the remains of site #10 in Steubenville include two sets of steps, a large ramp, and the lock esplanade. Pike Island Dam, meanwhile, has become a favorite spot for local fisherman.

Government Lock and Dam Site #10, 2012

Pike Island Lock and Dam, 2012

Steubenville’s Favorite Sons

At the time of TOG’s publication, there was no doubt that Edwin M. Stanton was the most revered figure in the city’s history. Two of the twelve points-of-interest in the printed guide relate directly to Stanton while the manuscript guide begins its tour of the region with the Edwin McMasters Stanton Home, the fourth such residence he occupied in the city.

Stanton was born in Steubenville in 1814. It was here he began a law career that would eventually lead him to Washington D.C. and an appointment as the Attorney General in President Buchanan’s Cabinet. In 1862, according to the manuscript guide, “President Lincoln made a master stroke in placing this influential Democrat in his cabinet as Secretary of War, thus helping to unify the Democrats in the north at the time of the Civil War.” After the war ended, Ulysses S. Grant appointed him to the Supreme Court. Unfortunately, like much of Grant’s presidency, things didn’t quite work out as planned as Stanton died four days after his appointment.

TOG cites a “bronze tablet on the doorway erected by the school children of the county,” as the source of its information regarding the birthplace of Stanton. 524 Market Street housed a jewelry store at the time of TOG’s publication, though this may have been irrelevant as “some say that he was born in the two-story brick structure [behind the store] now used as a warehouse and storage loft.” That jewelry store was one of the buildings across the street from the Imperial Hotel from the previous part of this section of the tour. While it is impossible to make out the bronze tablet, thanks to the resolution of the picture in the Ohio Guide Photograph Collection, you can see a sign which appears to read “Dr. Stanton” in the window of a building that would have sat at approximately 524 Market Street. This may be coincidence or perhaps one of Stanton’s relatives maintained an office in the building in which his (or possibly her) namesake was born. Either way it is a neat bit of continuity. The bronze tablet, meanwhile, can be found on a marble slab in a small landscaped area in front of an office building which can be seen in my rephotograph of the corner of Sixth and Market Streets.

Edwin Stanton birthplace with box indicating sign, @1940 / copyright OHS

"Dr. Stanton" sign, @1940 / copyright OHS

Birthplace of Edwin Stanton, 2012

Edwin Stanton Plaque, 2012

According to the manuscript guide, two years after Stanton’s birth in or behind the Market Street home, the family moved to a house “on the west side of North Third Street.” Soon after, his father died leaving the family in “straightened circumstances.” While this is not a phrase I am familiar with, apparently these are not the sorts of circumstances one wishes to be left in because “these trials Stanton overcame.” The surviving Stanton family moved once more before they settled into what the manuscript guide calls the Edwin McMasters Stanton Home. This red brick house on North Third and Dock Streets “was the finest residence in Steubenville,” when they moved into it 1844. Here Stanton kept cattle and “developed a fine garden…of fruit and vegetables….called ‘the Patch’ by the family.” “The Patch” has unfortunately given way to “the Parking Lot,” as the expansion of Route 7 required the elimination of most of N. Third Street, including Stanton’s home, and the area behind the house was given up for less pastoral purposes (though the building seen here is itself two hundred years old and is lovingly maintained by a resident who uses the old carriage house as a workshop for restoring his antique cars).

Site of "The Patch" behind Stanton residence, 2012

The most conspicuous memorial to Stanton and the second such point-of-interest in TOG is the Edwin M. Stanton Monument that sits in front of the Jefferson County Courthouse on Market Street. Unveiled in 1906 it is a “bronze likeness of Stanton making a speech at the courthouse.” Yes. So it is.

Edwin M. Stanton Monument, 2012

While the statue is unexceptional, its inclusion in TOG gives me the opportunity to share a wonderful photograph from the Guide Collection of Civil War veterans posing in front of it, albeit in a different location than it stands now (the photo also happens to be a favorite of Carla Zikursh, part of the OHS staff that has done so much work putting the Guide Collection together). A note on the back of the photograph reads: “The Last Roll Call. Civil War vets in front of Stanton’s statue. Sort of striking future all these are dead now. Can get their names if needed. -Jene E. Bishop.” It is worth zooming in on the full-size image to see the details of the mens’ accoutrements, including an electric hearing device worn by the man second from the right.

Stanton Statue with Civil War Vets, undated / copyright OHS

Stanton no longer claims the title of Steubenville’s most popular son. While my vote would go to Rollie Fingers, the mustachioed Hall of Fame relief pitcher who solidified the importance of a late inning “closer,” that honor now goes to the late entertainer Dean Martin. As a 2002 historical marker informs visitors traveling along Dean Martin Boulevard (Route 7 within the city limits), before teaming up with Jerry Lewis in the 1940s, Dino Crocetti worked in the steel mills of Steubenville and boxed under the name “Kid Crochet.”

For those interested in paying homage to Martin’s legacy, the Jefferson County Historical Museum and Library is in the midst of opening up a Dean Martin Room that will house memorabilia and documents pertaining to the performer. When Leonardo and I visited in April, Judy Brancazio and Mike Giles were overseeing the finishing touches of the room’s refurbishing. The JCHA is housed in the Sharpe Mansion, a beautiful structure on Franklin Ave. and contains nineteen rooms exhibiting furniture and eclectic artifacts from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. My favorite piece is this portrait of our 28th President. Piecing together pictures to form a new image is nothing new in this age of photoshop so it took me a second to realize the significance of what I was looking at as I stared at Wilson’s face. These are not individual pictures but individual people! This is a living collage of military personnel, choreographed to take the form of Woodrow Wilson. Titled “21,000 Officers and Man,” the scene was constructed at Camp Sherman in Chillicothe, Ohio in 1918. For more information on the historical museum and library, call 740.283.1133.

Woodrow Wilson Portrait from JCHM, 2012

Close-up of Woodrow Wilson Portrait

Fort Steuben and U.S. Land Office

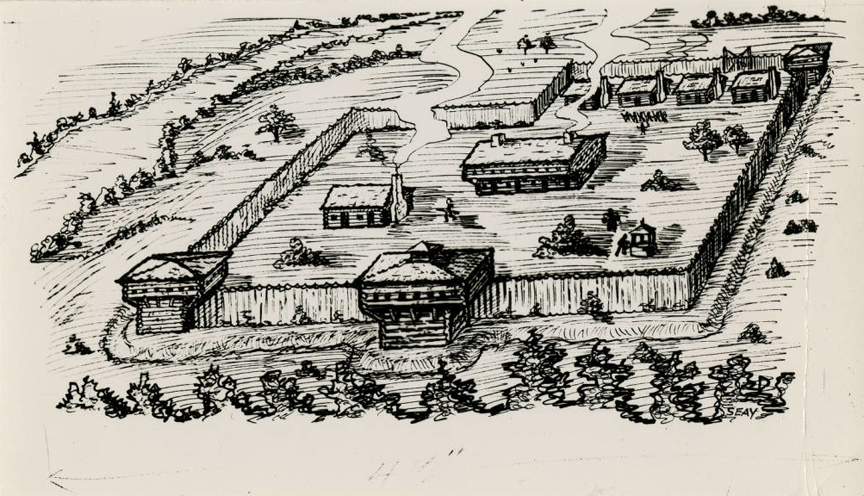

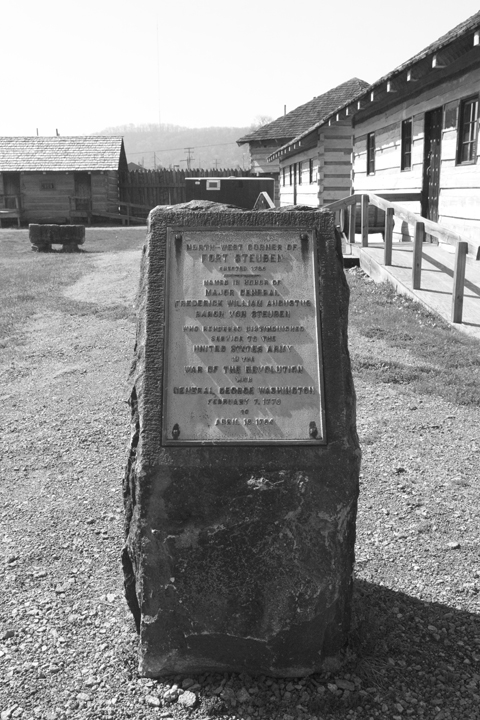

In Section A of this tour, I wrote about the Point of Beginning and Thomas Hutchins’ survey of the Seven Ranges. To protect Hutchins from Indian raids, members of the First American Regiment constructed Fort Steuben in 1786, named after Prussian officer Friedrich Wilhelm Augustus Heinrich Ferdinand (Baron von Steuben) who fought for the newly independent Americans during their war with England. Hutchins needed protection from Indians because during both the Seven-Years War (known by many school children as the French and Indian War) and the American Revolution, Ohio Indians found themselves on the losing side and were forced into signing a series of one-sided treaties. Though the treaties of Fort Stanwix, McIntosh, and Finney expressly forbade U.S. citizens from trespassing on what was left of Shawnee, Miami, Delaware, Ojibwe and Ottawa lands, such laws were rarely enforced, leaving many young Indian men little choice but to demonstrate their displeasure on the closest collection of American representatives.

This history and some really insightful thoughts on early setters’ relationships with Native Americans can be found in John R. Holmes’ The Story of Historic Fort Steuben, which was graciously given to me by Judy Bratton, the Executive Director of Historic Fort Steuben. Perhaps even more interesting than the construction of original fort, however, is Holmes’ telling of how the fort was built a second time over the period of twenty-years, from 1990 to 2010, after nearly two centuries of existing only the memory of the city’s residents. The reconstructed fort and new Fort Steuben Eastern Gateway Visitor’s Center was recently recognized for excellence in community involvement and innovation by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials: one of only eight such awards given nationally. It is must-see for those interested in early Ohio history.

At the time TOG was published, the tangible evidence of Fort Steuben was limited to four stone pillars with metal plates, indicating the four corners of the historic stockade. Two of these pillars have been moved within the walls of the new fort to protect them from vandals, while the other two have not been so fortunate.

In addition to giving me the book, Judy also gave Leonardo and I a personal tour of both the fort and the first U.S. Land Office of the Northwest Territory which now sits adjacent to it. Its history is even more convoluted than that of Fort Steuben, as described in the following two paragraphs taken from Holmes’ history:

On May 12, 1800, President John Adams appointed David Hoge the first registrar of the federal Land Office, the government body designated to record land deeds for the western expansion of the United States. …In 1801, Hoge built a one-room log cabin to serve as both his home and the recording office. He built it on Third Street, lot 104, about where the Steubenville Post Office is now. In 1809, Hoge moved the land office to lot 113, still on Third Street but now north of Washington, where it remained for twelve years. The cabin was small enough that Hoge probably found it easier simply to dismantle and reassemble the timbers rather than rebuild. In 1821, the building was moved to the northeast corner of Market and Alley A (now Court Street). In 1828, Hoge dismantled it again and moved it to South Third Street between Market and Adams. This was the final move for more than a century, since the little timber structure was bricked up and covered with a larger brick building. Not until the outer building was torn down in 1941 did people discover that the original beams of the 1801 house were preserved inside the brick walls of the building now scheduled for demolition (There is no indication of the building in the 1940-printed TOG, only a now-missing “marble stone a foot square, 10 feet above the pavement,” at 118 N. Third marking its former location. Generally very well edited, this levitating monument made it through the proof-reading process).

A few civic-minded people, realizing what they had discovered, tried to save the building. Eventually, they found space for it outside of town, in what is now Steubenville’s “West End,”…There it was used as a plane-spotting station during World War II. It remained a tourists attraction until 1963, when the cabin had to be moved again to accommodate the widening of Route 22. This time the history-minded leaders of Steubenville wanted to bring this piece of its past closer to its original home. The nearest strip of land vacant and controlled by the city was right on Route 7 near the Fort Steuben Bridge. Then, in 1976, it was Route 7’s turn to be widened , displacing the little cabin again. It moved farther south, still on Route 7, until that space was needed for the University Boulevard interchange for the new Veteran’s Memorial Bridge in 1983. Finally, Ohio Power found a home for it in the corner of its lot, exactly as it would do a few years later for Fort Steuben.

First U.S. Land Office in Northwest Territory, 2012

Mingo Junction

Even in 1940, Mingo Junction seemed more like an “extension of Steubenville than a city in its own right.” Like the Wheeling Steel Corporation to the north, the blast furnaces of Carnegie-Illinois Steel Mill emitted “fierce, flaming fire” which “lit up the night sky and their reflection on the river turns its murky color into hues of red and amber.” Yet unlike the Steubenville plant, the Carnegie-Illinois plant (now Wheeling-Pittsubrgh) continues to send “lurid rays into the night sky,” though not nearly as frequently as it once did. When Leonardo and I passed through town, it was the fading sunlight rather than the fire from the blast furnace which illuminated the “maze of mill structures.

Though its mill still produces some steel, Mingo Junction has not fared particularly well since the bottom fell out of the industry in the 1970s. Much of the downtown, while designated as a historic district, is abandoned and badly in need of repair. TOG points to Potter’s Spring, a natural spring George Washington and his party drank from while exploring the valley in 1770, as a site worth seeing on the south end of the now-historic neighborhood. Its current condition is a graphic illustration of just how much work needs to be done to restore the town to its quaint origins.

Potter's Spring, @1940 / copyright OHS

Potter's Spring, 2012

Potter's Spring, 2012

Mingo Junction was in a similar position at the time TOG was published. The Great Depression had reduced the economy to a fraction of what it was in the first quarter of the century, leaving the residence without any way to earn a living. The New Deal thus saved scores of towns like Mingo Junction whose citizens could work on local projects, rather than search the country for employment opportunities. Mill Creek Park, Beatty Park, and Steubenville High School were just a few of the places we have already visited on Tour 8 that were either built or drastically improved through New Deal programs.

Mingo Stadium was just such a project. Initiated by the Public Works Administration and still in planning stages when the manuscript guide was written, the “brick and cement stadium” was part of a large athletic complex which included “lockers and showers, baseball diamond, football field, track and tennis courts to be used by the High School and for general community sports, festivals and recreational activities.” I have not been able to determine when the stadium was torn down but today all that is left of the complex are the entrance arches and the remnants of an oval track in what is now an empty lot adjacent to Wheeling-Pittsburgh Steel. For other images of the stadium and some great trivia about Mingo Junction–What was Doc Cava’s first name and what kind of ties did he wear?–visit this intriguing site. I don’t know if the site is still updated as its homepage still announces it 10 year anniversary (1995-2005), but its creator obviously cares a great deal about the town.

Mingo Stadium Arches, 2012

Remnants of Track at Mingo Stadium, 2012

Just to the south of the stadium arches lies a huge expanse of railroad tracks. Running from Mingo Junction into the hamlet of George’s Run, this two-mile long rail-yard is full of cars in various states of disrepair. When the manuscript guide was written, the yard was owned by Central and Pacific Railroad and contained a round-house on the east side of the yard. Like the track of Mingo Stadium, the arch of the roundhouse foundation was relatively easy to locate against the disorder of regrowth. As I walked around the cement ring, I found railroad ties cut horizontally into three inch cross-sections and placed in the ground with the cut ends facing up and down. I assume they were placed this way so they would be harder to compress and this strategy seems to have worked as many of the wooden bricks remained in tact.

Foundation of Round House, 2012

Round House "Bricks", 2012

Ephraim Kimberly Land Grant and Stringer Mansion

With the exception of Yorkville whose “rows of company houses line the streets,” the twenty-or-so miles between Mingo Junction and Martin’s Ferry did not merit any acknowledgement in TOG. The manuscript guide, on the other hand, gives us an intriguing bit of history regarding a small stone with the inscription “E.K.” near the junction of Routes 7 and 150 in Rayland. This pillar, measuring fifteen inches square and about two feet tall, marked the southwest corner of a 400 acre land grant to captain Ephraim Kimberly for his services during Revolutionary War. The grant, signed by George Washington, is the first recorded instrument in the Deeds of Jefferson County.

While I was not able to find the pillar, I did find remnants of the Stringer Mansion which was built on the former land grant in 1836 by wealthy abolitionist John Brown Bayless. Jefferson Stringer, who had originally sold the land to Bayless, bought the land and mansion back in 1860 and lived there till his death. When the author of the manuscript guide passed through 1940, Stringer’s grandchildren still lived in the stone structure. Though the Stringer Mansion stood for many years , it burned down before it could fulfill the guide’s prophesy of standing for “100 more years.” Amanda Lynn and Kevin, two twenty-somethings I chatted with outside of the Dairy Queen adjacent to where I thought the mansion should be, say their siblings went on tours of the mansion as kids and confirmed my suspicion that the rocks lining the restaurant’s landscaping were once part of the mansion. While not the pastoral scene it was in 1940, there was still aspects of the “lingering loveliness” the guide described.

Stringer Stone House, @1940 / copyright OHS

Location of Stringer Stone House, 2012 / copyright David Bernstein

Tiltonsville Indian Mound

Many of the Euro-Americans who moved into the northern stretches of the Ohio Valley were intrigued by the remnants of the Hopewell and Adena peoples who lived there until @AD 500. While some of that interest resulted in the looting and destruction of burial mounds, it helped save others. In fact, according to John Holmes history of Fort Steuben, Colonel Harmar even instructed his officers to take careful notes and sketches of any antiquities they ran across. TOG is generally pretty good at including Hopewell and Adena sites (the most famous of which are Hopewell Cultural National Historic Site, Fort Ancient, and the Newark Earthworks) but the Tiltonsville Mound is not mentioned, not making the cut from the manuscript. It is a noteworthy cross-cultural creation, however, as Euro-American settlers incorporated their own burial practices into this ancient graveyard.

Tiltonsville Indian Mound, 2012

"The Sacred and the Propane", 2012

Martin’s Ferry

While its population of just over 7,000 is half of what it was at the time of TOGs publication, the description of this “steel and coal city…pushed against the river by the hills” is still as applicable in 2012 as it was in 1940: “Short cross streets connect its thoroughfares at different levels with squat brick-and-frame houses standing along them in drab series.” Named Martinsville by Ebenezer Martin in 1835, the town soon became known for its mode of transportation which ferried hogs, sheep and cattle across the Ohio on their way to Eastern markets.

TOG describes two points-of-interest in Martin’s Ferry, both of which pertain to the Zane family. Ebenezer Zane was, according to the inscription on his gravestone and the first point-of-interest, “the first permanent inhabitant of this part of the Western World, having first begun to reside here in 1769.” The tens of thousands of Indigenous peoples who had lived in the region notwithstanding, Zane gained historical prominence as the first settler of this part of the Northwest Territory and the surveyor of a former Indian trail that became known as Zane’s trace; an important transportation route that became part of the National Road in 1825.

His gravestone stands next to his wife’s, Elizabeth (Betty) Zane who is the focus of the second point-of-interest. In 1928, the “children of Martin’s Ferry” erected a statue at the entrance to Walnut Grove Cemetery “in memory of Elizabeth Zane whose heroic deed saved Fort Henry in 1782.” According to TOG, during a British and Indian siege of the fort, “at considerable risk, Betty Zane succeeded in carrying a supply of powder from a near-by house to the fort, thereby aiding in the repulse of the attackers.” I am not sure if this reveals more about gender roles in 1782 or 1928, but the sculpture’s size does prove that the children of Martin’s Ferry were very, very strong. Along with Union Cemetery in Steubenville, Walnut Grove Cemetery was one of the more picturesque stops on tour 8.

Bellaire

Between Walnut Grove Cemetery and the State Forest Nursery three miles north of Marietta, TOG lists only one point-of-interest: the House-that-Jack-Built in Bellaire. This three story brick house of “fading Victorian splendor” earned its title from a mule named Jack who carried the coal for its owner from valuable deposits nearby. To honor the beast of burden, the owner placed a small sculptured head of the mule above the front door. Unfortunately, the only hint I could find of the house was a 1982 historical novel in the window of the Imperial Glass Museum titled Eliza and the House that Jack Built (Imperial was one of the nation’s largest handmade glass manufacturing companies in the 20th century but for some reason was not included in TOG). The museum was closed so I was not able to thumb through the book, but the story of its author Albert Wass, is intriguing in its own right.

Perhaps because it was not a New Deal project, Bellaire’s most obvious historical point-of-interest, the Great Stone Viaduct, was left out of the publication. A 2008 plaque from the village of Bellaire and the Ohio Historical Society informs the reader that this railroad bridge consists of “43 stone arches supported by 47 ring stones (18 on each side of a keystone) intended to symbolize a united Union consisting of 37 states,” the number of such entities in 1871 when the viaduct was completed. This crossing was known, according to the plaque, as the “Great Shoreline to the West.”

Pulito Block" through Great Stone Viaduct, 2012

Union Street Station and Great Stone Viaduct, 2012

While the eighty-or-so miles between Martin’s Ferry and Marietta may have lacked points of interest, TOG offers some colorful descriptions. Near Dilles Bottom, for example, a “grotesquerie of coal cars, tracks, and tipples,” might be found radiating from a coal pit where “sober-faced men in dark clothes” tend to the “great smoldering mounds of slack.” The sulpherous odor, “often almost unbearable, permeates the atmosphere.” Such a smell could also be found a few miles later in Powhatan Point where “the highway passes neat frame houses and noxious mounds of slack.” For the author of this section of TOG, such was all he or she needed to see to understand the town:

Miners off duty, some of them helmeted and all of them in their work clothes, stand about the company store in small clusters, talking quietly or saying nothing at all. They talk without laughter and without discontent, their incurious lives bounded by their boxlike houses, the store, and the mines. A few have bandaged hands or missing limbs.

The perceived monotony of life in these small coal towns on the Ohio seems to have defeated the author of this section of the tour. After passing through Clarington (pop. 506) where “formerly clock-making was carried on,”(s)he writes “for the next 50 miles…small villages, inert or dying, appear: Hannibal (pop. 516); Duffy (pop. 75); Sardis (pop. 385); Fly (pop. 106), so named because the early settlers wanted their village to have a simple name.” Today, the numbers in these hamlets are even smaller than they were in 1940 and not going to increase any time soon. From Sardis down to Marietta, back from the river about fifteen miles, the area has been designated as part of Wayne National Forest.

Marietta

“No colony in America was ever settled under such favorable auspices,” George Washington once said of Marietta. Of course, having an economic stake in the Ohio Company of Associates which had just purchased the Northwest Territory from Congress, it is not that surprising that Washington would sing the praises of the newly created town at the confluence of the Ohio and Muskingham Rivers. Initially named Muskingham but then changed in honor of “Queen Marie Antoinette of France, whose nation had materially assisted the cause of the American Revolution” Marietta’s pioneers first landed across the Muskingham from three-year-old Fort Harmar in 1788. Here Rufus Putnam erected Campus Martius, “the strongest fortification in the territory of the United States,” according to a contemporary writer, where Governor Arthur St. Clair, Return Jonathan Meigs, Putnam, and approximately 300 settlers lived for the last decade of the eighteenth-century (According to TOG, Return got his name after his father proposed to the woman he loved. Seeing the heartbroken lad after initially refusing his request, “the young lady, suddenly remorseful, said pleadingly, ‘Return, Jonathan'”).

As the town grew into a primary stopping point for Ohio River traffic and a ship-building center in its own right, the fort was dismantled for its lumber and eventually all that was left of the original stockade was Rufus Putnams’ two-story house overlooking the Muskingham. In 1931, the Campus Martius Memorial State Museum was built around Putnam’s house. Soon after, the Northwest Territory Land Office, thought to be the oldest Euro-American-made building in the Northwest Territory, was moved to the museum site. Today, the museum houses three floors of exhibits on the establishment of the Northwest Territory. Along with a stone marking the Landing Place of the First Families at the foot of Washington Street, these three sites make up the first three points-of-interest in TOG.

Front Street in Marietta, 2012

Foot Bridge connecting Fort Harmar and Marietta, 2012

There is no doubt that Marietta is a quaint town. The description of a downtown where the modern “mingles with old and colorful…flavored with historic traditions,” is still as appropriate today as it was in 1940. Nearby, residences of “attractive old Colonial, Tudor, and Gothic houses have arisen unmistakably from the culture of New England.” Yet, particularly after driving through towns like East Liverpool and Steubenville, there is a sense that this history has been meticulously cultivated. In fact, even in 1940 “Mariettians [were] conscious and proud of their traditions. Endeavors [were] constantly being made to maintain a cultural standard in keeping with those pioneers who gave prehistoric earthwork names such as Capitolium and Quadranaou, and who designated these and other areas as parks so that they could be preserved” (Those other sites are Mound Cemetery, which TOG states also contains more officers of the American Revolution than any other cemetery in the country, and Sacra Via Park).

Mound Cemetery, @1940 / copyright OHS

Mound Cemetery, 2012

Preserving Adena and Hopewell sites is nothing Marietta should be ashamed of. Neither is their lovely downtown where virtually every building, historic or not, has a plaque stating its date of creation and original owner. Still, it is difficult to imagine “modern pioneers” of Steuvbenville re-enacting the journey of their city’s founders aboard duplicate vessels, as Mariettians did in 1938 to celebrate the town’s sesquicentennial. Or marking 150 years of civil government a few months later with a visit by President Roosevelt. Such showmanship was all but mocked in one of the manuscript versions of the Steubenville guide which stated that “unlike some towns which will go unnamed, Steubenville makes history rather than recreates it.” Whether the author was simply trying to prop up the morale of a city still in the throes of the Great Depression, or was passing on the sour-grapes sentiment of some of Steubenville’s residents, there is no doubt that there has been a deliberate effort by many of its citizens to establish Marietta as the most historically significant city in Ohio.

Evidence of this narrative-shaping can actually be found in the historical monuments themselves. At the corner of Front and Greene Streets stands Bicentennial Plaza, dedicated in 1987 to commemorate Marietta’s 200th birthday. Plaques and monuments explaining everything from shipbuilding to Indian wars dot this small look-out point at the junction of the Ohio and Muskingham Rivers. Two of the nine monuments also help explain why the monuments are there at all.

In 1824, Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de la Fayette, better known to the Americans he assisted during the Revolutionary War simply as Lafayette, returned to the United States where he “embarked on a unprecedented and triumphal TOUR,” according to one of the plaques in the plaza. In May of 1825, Lafayette “stopped overnight at the residence of Nahum Ward,” of Marietta before proceeding on to Pittsburgh. A plaque in Bicentennial Plaza cleverly leads the casual reader to believe that this uneventful stop marked “The Beginning of Tourism in the United States.” Nevermind that this stop was halfway into Lafayette’s trip, or that such tours were not that uncommon for European nobles in the first quarter of the nineteenth century, this plaque demonstrates a narrative tactic that I noticed in many of the town’s historical monuments: appropriating stories of a regional or national character and making them specific to Marietta’s history.

Bicentennial Plaza, Marietta, 2012

Monument to honor southern boundary of stockade, 2012

"Beginning of Tourism" , 2012

For example, during the same trip in which he marked 150 years of civil government in the Marietta, President Roosevelt also dedicated “A Memorial to the Start Westward of the United States” which contains both a statue and a set of steps leading down to the Muskingham. Similarly, a set of pillars leading into Muskingham Park highlights the Northwest Ordinance. As one of the first Euro-American communities established in the Northwest Territories, Marietta certainly has a legitimate claim to being an important addition to the growing American state. How it has been able to establish itself as either the starting point of Euro-American westward expansion or “The Place Where Ohio History Lives,” as its official guidebook declares, is another story.

Plan of Proposed Monument to Start of Westward Expansion, 1938 / copyright OHS

Start of Westward Expansion Monument, 2012

The very bottom of the Lafayette plaque bears the inscription, “This plaque erected 1959 by S. Durward Hoag, Innkeeper.” I did not think much about it until I looked at another small plaque partially hidden by a bush nearby. This one is a memorial to the very same S. Durward Hoag (1900-1982), erected by the Rotary Club of Marietta and reads “transportation and tourism visionary and owner of the Lafayette Hotel, ‘put Marietta on the map,’ by convincing the federal government to locate I-77 near historic Marietta.” This not only explains Hoag’s impetus for erecting the sign across from the street from his Lafayette Hotel which, though built nearly 100 years after Lafayette’s visit, he named in the Marquis’ honor, but also partially explains Marietta’s ability to focus its economy on historical tourism: it is easy to get to.

As I mentioned above, even in 1940, “Marietta ha[d] a dignity in keeping with her historic past.” Whether this was due to an economy that was able to escape the boom and bust cycle of other more industrial towns on the Ohio, or because it didn’t have the overwhelming identification with steel, or coal, or clay like Stuebenville or Mingo Junction or Toronto, Marietta made a concerted effort to highlight its past. Add to that the ability to attract travelers from Interstate 77, and you have the recipe for successfully commodifying your history. A brief comparison between Steubenville and Marietta shows just how important these factors can be.

Both towns were laid out under the auspices of military forts, Fort Harmar in 1785 and Fort Steuben in 1787. It would be Fort Steuben, however, that would have the stronger connection with Northwest Ordinance as it was that fort that was built to protect the surveyors of the Seven Ranges. While neither Fort Harmar nor Fort Steuben existed in 1940, the later has been reproduced and is now comparable to the Campus Martius museum in Marietta.

Much like Washington’s boast of the future site of Marietta, TOG claims that “old riverboat men pronounced Steubenville to be ‘the best town site on the Ohio’.” This site would hold the town of La Belle which grew up around Fort Steuben the same year it was constructed, one year before Marietta was established, making it the oldest Euro-American settlement in the Northwest Territory. While Marietta has the first Land Office erected in Northwest Territories (built by the Ohio Company and Associates) visitors can find the first U.S. Land Office of the Northwest Territory, built in 1800, on the grounds of the Fort Steuben Museum. Despite their similar origins, however, it has been Marietta that has established itself as the place to experience Ohio History.

Whether it was a more diversified economy, easier automobile access, or a citizenry more interested in its past, Marietta has a much firmer grip on Ohioans’ historic tourism business. Perhaps nothing epitomized this realization more than a trip up to Lookout Point, TOG’s last point-of-interest for Marietta. In the previous post, I wrote about the missing view from the top of Angel’s Trail in Steubenville and that it was not until I reached Marietta did I understand its importance. Both Angel’s Trial and Lookout Point were part of their towns’ common space, both established around the turn of the nineteenth century. In 1940, both were in condition enough to offer commanding views of the river valley and their respective historic towns below. Yet while Angel’s trail only offered a view of second growth when I climbed it, Lookout Point remained a well-maintained public space, complete with binoculars, and a view for miles. Indicating the economic importance of such tourist spots, the bottom of a plaque describing Lookout Point’s history bears the inscription, “Map and plaque manufactured by Sewah Studios, Marietta, OH.”

Lookout Point, Marietta, 2012

West, 2012